Calculator

A calculator is a small (often pocket-sized), usually inexpensive electronic device used to perform the basic operations of arithmetic. Modern calculators are more portable than most computers, though most PDAs are comparable in size to handheld calculators.

The calculator has its history in mechanical devices such as the abacus and slide rule. In the past, mechanical clerical aids such as abaci, comptometers, Napier's bones, books of mathematical tables, slide rules, or mechanical adding machines were used for numeric work. This semi-manual process of calculation was tedious and error-prone. The first digital mechanical calculator was invented in 1623 and the first commercially successful device was produced in 1820. The 19th and early 20th centuries saw improvements to the mechnical design, in parallel with analog computers; the first digital electronic calculators were created in the 1960s, with pocket-sized devices becoming available in the 1970s.

Modern calculators are electrically powered (usually by battery and/or solar cell) and vary from cheap, give-away, credit-card sized models to sturdy adding machine-like models with built-in printers. They first became popular in the late 1960s as decreasing size and cost of electronics made possible devices for calculations, avoiding the use of scarce and expensive computer resources. By the 1980s, calculator prices had reduced to a point where a basic calculator was affordable to most. By the 1990s they had become common in math classes in schools, with the idea that students could be freed from basic calculations and focus on the concepts.

Computer operating systems as far back as early Unix have included interactive calculator programs such as dc and hoc, and calculator functions are included in almost all PDA-type devices (save a few dedicated address book and dictionary devices).

In addition to general purpose calculators, there are those designed for specific markets; for example, there are scientific calculators which focus on operations slightly more complex than those specific to arithmetic - for instance, trigonometric and statistical calculations. Some calculators even have the ability to do computer algebra. Graphing calculators can be used to graph functions defined on the real line, or higher dimensional Euclidean space. They often serve other purposes, however.

Contents |

Design

Most calculators contain the following buttons: 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,0,+,-,×,÷ (/),.,=,%, and ± (+/-). Some even contain 00 and 000 buttons to make larger calculations easier to compute.

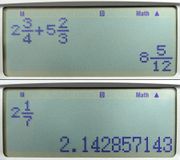

Some fractions such as 2⁄3 are awkward to display on a calculator display as they are usually rounded to 0.66666667. Also, some fractions such as 1⁄7 which is 0.14285714285714 (to fourteen significant figures) can be difficult to recognize in decimal form; as a result, many scientific calculators are able to work in vulgar fractions and/or mixed numbers.

In most countries, students use calculators for schoolwork. There was some initial resistance to the idea out of fear that basic arithmetic skills would suffer. There remains disagreement about the importance of the ability to perform calculations "in the head", with some curricula restricting calculator use until a certain level of proficiency has been obtained, while others concentrate more on teaching estimation techniques and problem-solving. Research suggests that inadequate guidance in the use of calculating tools can restrict the kind of mathematical thinking that students engage in.[1] Others have argued that calculator use can even cause core mathematical skills to atrophy, or that such use can prevent understanding of advanced algebraic concepts.

Calculators versus computers

The fundamental difference between a calculator and computer is that a computer can be programmed in a way that allows the program to take different branches according to intermediate results, while calculators are pre-designed with specific functions such as addition, multiplication, and logarithms built in. The distinction is not clear-cut: some devices classed as programmable calculators have programming functionality, sometimes with support for programming languages such as RPL or TI-BASIC.

Typically the user buys the least expensive model having a specific feature set, but does not care much about speed (since speed is constrained by how fast the user can press the buttons). Thus designers of calculators strive to minimize the number of logic elements on the chip, not the number of clock cycles needed to do a computation.

For instance, instead of a hardware multiplier, a calculator might implement floating point mathematics with code in ROM, and compute trigonometric functions with the CORDIC algorithm because CORDIC does not require hardware floating-point. Bit serial logic designs are more common in calculators whereas bit parallel designs dominate general-purpose computers, because a bit serial design minimizes chip complexity, but takes many more clock cycles. (Again, the line blurs with high-end calculators, which use processor chips associated with computer and embedded systems design, particularly the Z80, MC68000, and ARM architectures, as well as some custom designs specifically made for the calculator market.)

History

Origin: the abacus

The first calculators were abathia, and were often constructed as a wooden frame with beads sliding on wires. Abathias were in use centuries before the adoption of the written Arabic numerals system and are still used by some merchants, fishermen and clerks in Africa, Asia, and elsewhere.

Other early calculators

Devices have been used to aid computation for thousands of years, using one-to-one correspondence with our fingers.[2] The earliest counting device was probably a form of tally stick. Later record keeping aids throughout the Fertile Crescent included clay shapes, which represented counts of items, probably livestock or grains, sealed in containers.[3]

The counter abacus was devised by Egyptian mathematicians in Egypt in 2000 BC. It was used for arithmetic tasks. The Roman abacus was used in Babylonia as early as 2400 BC. Since then, many other forms of reckoning boards or tables have been invented. In a medieval counting house, a checkered cloth would be placed on a table, and markers moved around on it according to certain rules, as an aid to calculating sums of money (this is the origin of "Exchequer" as a term for a nation's treasury).

A number of analog computers were constructed in ancient and medieval times to perform astronomical calculations. These include the Antikythera mechanism and the astrolabe from ancient Greece (c. 150-100 BC), which are generally regarded as the first mechanical analog computers.[4] Other early versions of mechanical devices used to perform some type of calculations include the planisphere and other mechanical computing devices invented by Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī (c. AD 1000); the equatorium and universal latitude-independent astrolabe by Abū Ishāq Ibrāhīm al-Zarqālī (c. AD 1015); the astronomical analog computers of other medieval Muslim astronomers and engineers; and the astronomical clock tower of Su Song (c. AD 1090) during the Song Dynasty. The "castle clock", an astronomical clock invented by Al-Jazari in 1206, is considered to be the earliest programmable analog computer.[5]

The 17th century

Scottish mathematician and physicist John Napier noted multiplication and division of numbers could be performed by addition and subtraction, respectively, of logarithms of those numbers. While producing the first logarithmic tables Napier needed to perform many multiplications, and it was at this point that he designed Napier's bones, an abacus-like device used for multiplication and division.[6]

In 1622 William Oughtred invented the slide rule, which was revealed by his student Richard Delamain in 1630.[7] Since real numbers can be represented as distances or intervals on a line, the slide rule allows multiplication and division operations to be carried out significantly faster than was previously possible.[8] The devices were used by generations of engineers and other mathematically inclined professional workers, until the invention of the pocket calculator. The engineers in the Apollo program that sent a man to the moon made many of their calculations on slide rules, which were accurate to three or four significant figures.[9]

Wilhelm Schickard, a German polymath, designed a calculating clock in 1623; unfortunately a fire destroyed it during its construction in 1624 and Schickard abandoned his project. Two sketches of it were discovered in 1957; too late to have any impact on the development of mechanical calculators[10].

In 1642, while still a teenager, Blaise Pascal started some pioneering work on calculating machines and after three years of effort and 50 prototypes[11] he invented the mechanical calculator[12][13]. He built twenty of these machines (called the Pascaline) in the following ten years[14].

Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz invented the Stepped Reckoner and his famous cylinders around 1672 while adding direct multiplication and division to the Pascaline. Leibniz once said "It is unworthy of excellent men to lose hours like slaves in the labour of calculation which could safely be relegated to anyone else if machines were used."[15]

The 19th century

Machines in production

- in 1820 Thomas de Colmar invented the Arithmometer which was the first commercially successful mechanical calculator. Its sturdy design gave it a strong reputation of reliability and accuracy[16] and its production debut of 1851 launched the mechanical calculator industry[17].

- Dorr E. Felt, in the U.S., invented the Comptometer in 1886, the first successful key-driven adding and calculating machine ["key-driven" refers to the fact that just pressing the keys causes the result to be calculated, no separate lever has to be operated]. In 1887[18] he joined with Robert Tarrant to form the Felt & Tarrant Manufacturing Company which went on to make thousands of Comptometers.

- in 1878 W.T. Odhner invented the Odhner Arithmometer which was the redesigned version of the Arithmometer with a pinwheel engine but with the same user interface. Many companies, all over the world, manufactured clones of this machine and millions were sold well into the 1970s.[19]

- In 1892 William S. Burroughs began commercial manufacture of his printing adding calculator[20] Burroughs Corporation became one of the leading companies in the accounting machine and computer businesses.

- The "Millionaire" calculator was introduced in 1893. It allowed direct multiplication by any digit - "one turn of the crank for each figure in the multiplier".

Prototypes and limited runs

- In 1822 Charles Babbage designed a mechanical calculator, called a difference engine, which was capable of holding and manipulating seven numbers of 31 decimal digits each. Babbage produced two designs for the difference engine and a further design for a more advanced mechanical programmable computer called an analytical engine. None of these designs were completely built by Babbage. In 1991 the London Science Museum followed Babbage's plans to build a working difference engine using the technology and materials available in the 19th century.

- In 1842, Timoleon Maurel invented the Arithmaurel, based on the Arithmometer, which could multiply two numbers by simply entering their values into the machine.

- In 1853 Per Georg Scheutz completed a working difference engine based on Babbage's design. The machine was the size of a piano, and was demonstrated at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1855. It was used to create tables of logarithms.

- In 1872, Frank S. Baldwin in the U.S. invented a pinwheel calculator.

- In 1875 Martin Wiberg re-designed the Babbage/Scheutz difference engine and built a version that was the size of a sewing machine.

1900s to 1960s

Mechanical calculators reach their zenith

The first half of the 20th century saw the gradual development of the mechanical calculator mechanism.

The Dalton adding-listing machine introduced in 1902 was the first of its type to use only ten keys, and became the first of many different models of "10-key add-listers" manufactured by many companies.

In 1948 the miniature Curta calculator, which was held in one hand for operation, was introduced after being developed by Curt Herzstark in 1938. This was an extreme development of the stepped-gear calculating mechanism.

From the early 1900s through the 1960s, mechanical calculators dominated the desktop computing market (see History of computing hardware). Major suppliers in the USA included Friden, Monroe, and SCM/Marchant. (Some comments about European calculators follow below.) These devices were motor-driven, and had movable carriages where results of calculations were displayed by dials. Nearly all keyboards were full — each digit that could be entered had its own column of nine keys, 1..9, plus a column-clear key, permitting entry of several digits at once. (See the illustration of a 1914 mechanical calculator.) One could call this parallel entry, by way of contrast with ten-key serial entry that was commonplace in mechanical adding machines, and is now universal in electronic calculators. (Nearly all Friden calculators had a ten-key auxiliary keyboard for entering the multiplier when doing multiplication.) Full keyboards generally had ten columns, although some lower-cost machines had eight. Most machines made by the three companies mentioned did not print their results, although other companies, such as Olivetti, did make printing calculators.

In these machines, addition and subtraction were performed in a single operation, as on a conventional adding machine, but multiplication and division were accomplished by repeated mechanical additions and subtractions. Friden made a calculator that also provided square roots, basically by doing division, but with added mechanism that automatically incremented the number in the keyboard in a systematic fashion. Friden and Marchant (Model SKA) made calculators with square root. Handheld mechanical calculators such as the 1948 Curta continued to be used until they were displaced by electronic calculators in the 1970s.

Triumphator CRN1 (1958)

|

Walther WSR160 (1960)

|

Dalton adding machine (1930 ca.)

|

Typical European four-operations machines use the Odhner mechanism, or variations of it. This kind of machines included the Original Odhner, Brunsviga and several following imitators, starting from Triumphator, Thales, Walther, Facit up to Toshiba. Although most of these was operated by handcranks, there were motor-driven versions.

Although Dalton introduced in 1902 first ten-keys printing adding(two operations) machine, these features was not present in computing (four operations) machines for many decades. Facit-T (1932) was the first 10-keys computing machine having a large commercial diffusion. Olivetti Divisumma-14 (1948) was the first computing machine with both printer and 10-keys keyboard. Full-keyboard machines, including motor-driven ones, were also built until 60ties. Some machines had as many as 20 columns in their full keyboards. The monster in this field was the Duodecillion made by Burroughs for exhibit purposes.

Duodecillion (1915 ca.)

|

Marchant Figurematic (1950-52)

|

Facit NTK (1954)

|

Olivetti Divisumma 24 (1964)

|

The development of electronic calculators

The first mainframe computers, using firstly vacuum tubes and later transistors in the logic circuits, appeared in the 1940s and 1950s. This technology was to provide a stepping stone to the development of electronic calculators.

In 1954 IBM, in the U.S., demonstrated a large all-transistor calculator and, in 1957, the company released the first commercial all-transistor calculator, the IBM 608, though it was housed in several cabinets and cost about $80,000.[21]

The Casio Computer Co., in Japan, released the Model 14-A calculator in 1957, which was the world's first all-electric (relatively) "compact" calculator. It did not use electronic logic but was based on relay technology, and was built into a desk.

In October 1961 the world's first all-electronic desktop calculator, the British Bell Punch/Sumlock Comptometer ANITA (A New Inspiration To Arithmetic/Accounting) was announced.[22][23] This machine used vacuum tubes, cold-cathode tubes and Dekatrons in its circuits, with 12 cold-cathode "Nixie"-type tubes for its display. Two models were displayed, the Mk VII for continental Europe and the Mk VIII for Britain and the rest of the world, both for delivery from early 1962. The Mk VII was a slightly earlier design with a more complicated mode of multiplication, and was soon dropped in favour of the simpler Mark VIII. The ANITA had a full keyboard, similar to mechanical comptometers of the time, a feature that was unique to it and the later Sharp CS-10A among electronic calculators. Bell Punch had been producing key-driven mechanical calculators of the comptometer type under the names "Plus" and "Sumlock", and had realised in the mid-1950s that the future of calculators lay in electronics. They employed the young graduate Norbert Kitz, who had worked on the early British Pilot ACE computer project, to lead the development. The ANITA sold well since it was the only electronic desktop calculator available, and was silent and quick.

The tube technology of the ANITA was superseded in June 1963 by the U.S. manufactured Friden EC-130, which had an all-transistor design, 13-digit capacity on a 5-inch CRT, and introduced reverse Polish notation (RPN) to the calculator market for a price of $2200, which was about three times the cost of an electromechanical calculator of the time. Like Bell Punch, Friden was a manufacturer of mechanical calculators that had decided that the future lay in electronics. In 1964 more all-transistor electronic calculators were introduced: Sharp introduced the CS-10A, which weighed 25 kg (55 lb) and cost 500,000 yen (~US$2500), and Industria Macchine Elettroniche of Italy introduced the IME 84, to which several extra keyboard and display units could be connected so that several people could make use of it (but apparently not at the same time).

There followed a series of electronic calculator models from these and other manufacturers, including Canon, Mathatronics, Olivetti, SCM (Smith-Corona-Marchant), Sony, Toshiba, and Wang. The early scalculators used hundreds of germanium transistors, which were cheaper than silicon transistors, on multiple circuit boards. Display types used were CRT, cold-cathode Nixie tubes, and filament lamps. Memory technology was usually based on the delay line memory or the magnetic core memory, though the Toshiba "Toscal" BC-1411 appears to have used an early form of dynamic RAM built from discrete components. Already there was a desire for smaller and less power-hungry machines.

The Olivetti Programma 101 was introduced in late 1965; it was a stored program machine which could read and write magnetic cards and displayed results on its built-in printer. Memory, implemented by an acoustic delay line, could be partitioned between program steps, constants, and data registers. Programming allowed conditional testing and programs could also be overlaid by reading from magnetic cards. It is regarded as the first personal computer produced by a company (that is, a desktop electronic calculating machine programmable by non-specialists for personal use). The Olivetti Programma 101 won many industrial design awards.

The Monroe Epic programmable calculator came on the market in 1967. A large, printing, desk-top unit, with an attached floor-standing logic tower, it could be programmed to perform many computer-like functions. However, the only branch instruction was an implied unconditional branch (GOTO) at the end of the operation stack, returning the program to its starting instruction. Thus, it was not possible to include any conditional branch (IF-THEN-ELSE) logic. During this era, the absence of the conditional branch was sometimes used to distinguish a programmable calculator from a computer.

The first handheld calculator was developed by Texas Instruments in 1967. It could add, multiply, subtract, and divide, and its output device was a paper tape.[24][25]

1970s to mid-1980s

The electronic calculators of the mid-1960s were large and heavy desktop machines due to their use of hundreds of transistors on several circuit boards with a large power consumption that required an AC power supply. There were great efforts to put the logic required for a calculator into fewer and fewer integrated circuits (chips) and calculator electronics was one of the leading edges of semiconductor development. U.S. semiconductor manufacturers led the world in Large Scale Integration (LSI) semiconductor development, squeezing more and more functions into individual integrated circuits. This led to alliances between Japanese calculator manufacturers and U.S. semiconductor companies: Canon Inc. with Texas Instruments, Hayakawa Electric (later known as Sharp Corporation) with North-American Rockwell Microelectronics, Busicom with Mostek and Intel, and General Instrument with Sanyo.

Pocket calculators

By 1970, a calculator could be made using just a few chips of low power consumption, allowing portable models powered from rechargeable batteries. The first portable calculators appeared in Japan in 1970, and were soon marketed around the world. These included the Sanyo ICC-0081 "Mini Calculator", the Canon Pocketronic, and the Sharp QT-8B "micro Compet". The Canon Pocketronic was a development of the "Cal-Tech" project which had been started at Texas Instruments in 1965 as a research project to produce a portable calculator. The Pocketronic has no traditional display; numerical output is on thermal paper tape. As a result of the "Cal-Tech" project, Texas Instruments was granted master patents on portable calculators.

Sharp put in great efforts in size and power reduction and introduced in January 1971 the Sharp EL-8, also marketed as the Facit 1111, which was close to being a pocket calculator. It weighed about one pound, had a vacuum fluorescent display, rechargeable NiCad batteries, and initially sold for $395.

However, the efforts in integrated circuit development culminated in the introduction in early 1971 of the first "calculator on a chip", the MK6010 by Mostek,[26] followed by Texas Instruments later in the year. Although these early hand-held calculators were very expensive, these advances in electronics, together with developments in display technology (such as the vacuum fluorescent display, LED, and LCD), lead within a few years to the cheap pocket calculator available to all.

In early 1971 Pico Electronics.[27] and General Instrument also introduced their first collaboration in ICs, a complete single chip calculator IC for the Monroe Royal Digital III calculator. Pico was a spinout by five GI design engineers whose vision was to create single chip calculator ICs. Pico and GI went on to have significant success in the burgeoning handheld calculator market.

The first truly pocket-sized electronic calculator was the Busicom LE-120A "HANDY", which was marketed early in 1971[28]. Made in Japan, this was also the first calculator to use an LED display, the first hand-held calculator to use a single integrated circuit (then proclaimed as a "calculator on a chip"), the Mostek MK6010, and the first electronic calculator to run off replaceable batteries. Using four AA-size cells the LE-120A measures 4.9x2.8x0.9 in (124x72x24 mm).

The first American-made pocket-sized calculator, the Bowmar 901B (popularly referred to as The Bowmar Brain), measuring 5.2×3.0×1.5 in (131×77×37 mm), came out in the fall of 1971, with four functions and an eight-digit red LED display, for $240, while in August 1972 the four-function Sinclair Executive became the first slimline pocket calculator measuring 5.4×2.2×0.35 in (138×56×9 mm) and weighing 2.5 oz (70g). It retailed for around $150 (GB£79). By the end of the decade, similar calculators were priced less than $10 (GB£5).

The first Soviet-made pocket-sized calculator, the "Elektronika B3-04" was developed by the end of 1973 and sold at the beginning of 1974.

One of the first low-cost calculators was the Sinclair Cambridge, launched in August 1973. It retailed for GB£29.95, or £5 less in kit form. The Sinclair calculators were successful because they were far cheaper than the competition; however, their design was flawed and their accuracy in some functions was questionable. The scientific programmable models were particularly poor in this respect, with the programmability coming at a heavy price in Transcendental function accuracy.

Meanwhile Hewlett Packard (HP) had been developing its own pocket calculator. Launched in early 1972 it was unlike the other basic four-function pocket calculators then available in that it was the first pocket calculator with scientific functions that could replace a slide rule. The $395 HP-35, along with all later HP engineering calculators, used reverse Polish notation (RPN), also called postfix notation. A calculation like "8 plus 5" is, using RPN, performed by pressing "8", "Enter↑", "5", and "+"; instead of the algebraic infix notation: "8", "+", "5", "=").

The first Soviet scientific pocket-sized calculator the "B3-18" was completed by the end of 1975.

In 1973, Texas Instruments(TI) introduced the SR-10, (SR signifying slide rule) an algebraic entry pocket calculator for $150. It was followed the next year by the SR-50 which added log and trig functions to compete with the HP-35, and in 1977 the mass-marketed TI-30 line which is still produced.

In 1978 a new company, Calculated Industries, came onto the scene, focusing on specific markets. Their first calculator, the Loan Arranger [29](1978) was a pocket calculator marketed to the Real Estate industry with preprogrammed functions to simplify the process of calculating payments and future values. In 1985, CI launched a calculator for the construction industry called the Construction Master [30] which came preprogrammed with common construction calculations (such as angles, stairs, roofing math, pitch, rise, run, and feet-inch fraction conversions). This would be the first in a line of construction related calculators.

Programmable calculators

The first desktop programmable calculators were produced in the mid-1960s by Mathatronics and Casio (AL-1000). These machines were, however, very heavy and expensive. The first programmable pocket calculator was the HP-65, in 1974; it had a capacity of 100 instructions, and could store and retrieve programs with a built-in magnetic card reader. Two years later the HP-25C introduced continuous memory, i.e. programs and data were retained in CMOS memory during power-off. In 1979, HP released the first alphanumeric, programmable, expandable calculator, the HP-41C. It could be expanded with RAM (memory) and ROM (software) modules, as well as peripherals like bar code readers, microcassette and floppy disk drives, paper-roll thermal printers, and miscellaneous communication interfaces (RS-232, HP-IL, HP-IB).

The first Soviet programmable desktop calculator ISKRA 123, powered by the power grid, was released at he beginning of the 1970s. The first Soviet pocket battery-powered programmable calculator, Elektronika "B3-21", was developed by the end of 1977 and released at the beginning of 1978. The successor of B3-21, the Elektronika B3-34 wasn't backward compatible with B3-21, even if it kept the reverse Polish notation (RPN). Thus B3-34 defined a new command set, which later was used in a series of later programmable Soviet calculators. Despite very limited capabilities (98 bytes of instruction memory and about 19 stack and addressable registers), people managed to write all kinds of programs for them, including adventure games and libraries of calculus-related functions for engineers. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of programs were written for these machines, from practical scientific and business software, which were used in real-life offices and labs, to fun games for children. The Elektronika MK-52 calculator (using the extended B3-34 command set, and featuring internal EEPROM memory for storing programs and external interface for EEPROM cards and other periphery) was used in Soviet spacecraft program (for Soyuz TM-7 flight) as a backup of the board computer.

This series of calculators was also noted for a large number of highly counter-intuitive mysterious undocumented features, somewhat similar to "synthetic programming" of the American HP-41, which were exploited by applying normal arithmetic operations to error messages, jumping to non-existent addresses and other techniques. A number of respected monthly publications, including the popular science magazine "Наука и жизнь" ("Science and Life"), featured special columns, dedicated to optimization techniques for calculator programmers and updates on undocumented features for hackers, which grew into a whole esoteric science with many branches, known as "eggogology" ("еггогология"). The error messages on those calculators appear as a Russian word "EGGOG" ("ЕГГОГ") which, unsurprisingly, is translated to "Error".

A similar hacker culture in the USA was centered around the HP-41, which was also noted for a large number of undocumented features and was much more powerful than B3-34.

Mechanical calculators

Mechanical calculators continued to be sold, though in rapidly decreasing numbers, into the early 1970s, with many of the manufacturers closing down or being taken over. Comptometer type calculators were often retained for much longer to be used for adding and listing duties, especially in accounting, since a trained and skilled operator could enter all the digits of a number in one movement of the hands on a Comptometer quicker than was possible serially with a 10-key electronic calculator. The spread of the computer rather than the simple electronic calculator put an end to the Comptometer. Also, by the end of the 1970s, the slide rule had become obsolete.

Technical improvements

Through the 1970s the hand-held electronic calculator underwent rapid development. The red LED and blue/green vacuum fluorescent displays consumed a lot of power and the calculators either had a short battery life (often measured in hours, so rechargeable nickel-cadmium batteries were common) or were large so that they could take larger, higher capacity batteries. In the early 1970s liquid crystal displays (LCDs) were in their infancy and there was a great deal of concern that they only had a short operating lifetime. Busicom introduced the Busicom LE-120A "HANDY" calculator, the first pocket-sized calculator and the first with an LED display, and announced the Busicom LC with LCD display. However, there were problems with this display and the calculator never went on sale. The first successful calculators with LCDs were manufactured by Rockwell International and sold from 1972 by other companies under such names as: Dataking LC-800, Harden DT/12, Ibico 086, Lloyds 40, Lloyds 100, Prismatic 500 (aka P500), Rapid Data Rapidman 1208LC. The LCDs were an early form with the numbers appearing as silver against a dark background. To present a high-contrast display these models illuminated the LCD using a filament lamp and solid plastic light guide, which negated the low power consumption of the display. These models appear to have been sold only for a year or two.

A more successful series of calculators using the reflective LCD display was launched in 1972 by Sharp Inc with the Sharp EL-805, which was a slim pocket calculator. This, and another few similar models, used Sharp's "COS" (Crystal on Substrate) technology. This used a glass-like circuit board which was also an integral part of the LCD. In operation the user looked through this "circuit board" at the numbers being displayed. The "COS" technology may have been too expensive since it was only used in a few models before Sharp reverted to conventional circuit boards, though all the models with the reflective LCD displays are often referred to as "COS".

In the mid-1970s the first calculators appeared with the now "normal" LCDs with dark numerals against a grey background, though the early ones often had a yellow filter over them to cut out damaging ultraviolet rays. The advantage of the LCD is that it is passive and reflects light, which requires much less power than generating light. This led the way to the first credit-card-sized calculators, such as the Casio Mini Card LC-78 of 1978, which could run for months of normal use on button cells.

There were also improvements to the electronics inside the calculators. All of the logic functions of a calculator had been squeezed into the first "Calculator on a chip" integrated circuits in 1971, but this was leading edge technology of the time and yields were low and costs were high. Many calculators continued to use two or more integrated circuits (ICs), especially the scientific and the programmable ones, into the late 1970s.

The power consumption of the integrated circuits was also reduced, especially with the introduction of CMOS technology. Appearing in the Sharp "EL-801" in 1972, the transistors in the logic cells of CMOS ICs only used any appreciable power when they changed state. The LED and VFD displays often required additional driver transistors or ICs, whereas the LCD displays were more amenable to being driven directly by the calculator IC itself.

With this low power consumption came the possibility of using solar cells as the power source, realised around 1978 by such calculators as the Royal Solar 1, Sharp EL-8026, and Teal Photon.

A pocket calculator for everyone

At the beginning of the 1970s hand-held electronic calculators were very expensive, costing two or three weeks' wages, and so were a luxury item. The high price was due to their construction requiring many mechanical and electronic components which were expensive to produce, and production runs were not very large. Many companies saw that there were good profits to be made in the calculator business with the margin on these high prices. However, the cost of calculators fell as components and their production techniques improved, and the effect of economies of scale were felt.

By 1976 the cost of the cheapest 4-function pocket calculator had dropped to a few dollars, about one twentieth of the cost five years earlier. The consequences of this were that the pocket calculator was affordable, and that it was now difficult for the manufacturers to make a profit out of calculators, leading to many companies dropping out of the business or closing down altogether. The companies that survived making calculators tended to be those with high outputs of higher quality calculators, or producing high-specification scientific and programmable calculators.

Mid-1980s to present

The first calculator capable of symbolic computation was the HP-28C, released in 1987. It was able to, for example, solve quadratic equations symbolically. The first graphing calculator was the Casio FX-7000G released in 1985.

The two leading manufacturers, HP and TI, released increasingly feature-laden calculators during the 1980s and 1990s. At the turn of the millennium, the line between a graphing calculator and a handheld computer was not always clear, as some very advanced calculators such as the TI-89, the Voyage 200 and HP-49G could differentiate and integrate functions, solve differential equations, run word processing and PIM software, and connect by wire or IR to other calculators/computers.

The HP 12c financial calculator is still produced. It was introduced in 1981 and is still being made with few changes. The HP 12c featured the reverse Polish notation mode of data entry. In 2003 several new models were released, including an improved version of the HP 12c, the "HP 12c platinum edition" which added more memory, more built-in functions, and the addition of the algebraic mode of data entry.

Calculated Industries competed with the HP 12c in the mortgage and real estate markets by differentiating the key labeling; changing the “I”, “PV”, “FV” to easier labeling terms such as "Int", "Term", "Pmt", and not using the reverse Polish notation. However, CI's more successful calculators involved a line of construction calculators, which evolved and expanded in the 90's to present. According to Mark Bollman [31], a mathematics and calculator historian and associate professor of mathematics at Albion College, the "Construction Master is the first in a long and profitable line of CI construction calculators" which carried them through the 1980s, 1990s, and to the present.

Personal computers often come with a calculator utility program that emulates the appearance and functionality of a calculator, using the graphical user interface to portray a calculator. One such example is Windows Calculator

See also

- History of computing hardware

- Beghilos

- Formula calculator

- Software calculator

- List of HP calculators

Notes

- ↑ Thomas J. Bing, Edward F. Redish, Symbolic Manipulators Affect Mathematical Mindsets, December 2007

- ↑ Georges Ifrah notes that humans learned to count on their hands. Ifrah shows, for example, a picture of Boethius (who lived 480–524 or 525) reckoning on his fingers in Ifrah 2000, p. 48.

- ↑ According to Schmandt-Besserat 1981, these clay containers contained tokens, the total of which were the count of objects being transferred. The containers thus served as a bill of lading or an accounts book. In order to avoid breaking open the containers, marks were placed on the outside of the containers, for the count. Eventually (Schmandt-Besserat estimates it took 4000 years) the marks on the outside of the containers were all that were needed to convey the count, and the clay containers evolved into clay tablets with marks for the count.

- ↑ Lazos 1994

- ↑ Ancient Discoveries, Episode 11: Ancient Robots. History Channel. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rxjbaQl0ad8. Retrieved 2008-09-06

- ↑ A Spanish implementation of Napier's bones (1617), is documented in Montaner i Simon 1887, pp. 19–20.

- ↑ Slide Rules

- ↑ Kells, Kern & Bland 1943, p. 92

- ↑ Kells, Kern & Bland 1943, p. 82, as log(2)=.3010, or 4 places.

- ↑ René Taton, p. 81 (1969)

- ↑ (fr) La Machine d’arithmétique, Blaise Pascal, Wikisource

- ↑ Jean Marguin (1994), p. 48

- ↑ Maurice d'Ocagne (1893), p. 245 Copy of this book found on the CNAM site

- ↑ Guy Mourlevat, p. 12 (1988)

- ↑ As quoted in Smith 1929, pp. 180–181

- ↑ Ifrah G., The Universal History of Numbers, vol 3, page 127, The Harvill Press, 2000

- ↑ Chase G.C.: History of Mechanical Computing Machinery, Vol. 2, Number 3, July 1980, IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, p. 204

- ↑ J.A.V. Turck, Origin of modern calculating machines, The western society of engineers, 1921, p. 75

- ↑ Trogemann G., Nitussov A.: Computing in Russia, GWV-Vieweg, 2001, ISBN 3-528-05757-2, p. 45

- ↑ J.A.V. Turck, Origin of modern calculating machines, The western society of engineers, 1921, p. 143

- ↑ IBM Archives: IBM 608 calculator

- ↑ "Simple and Silent", Office Magazine, December 1961, p1244

- ↑ "'Anita' der erste tragbare elektonische Rechenautomat" [trans: "the first portable electronic computer"], Buromaschinen Mechaniker, November 1961, p207

- ↑ Texas Instruments Celebrates the 35th Anniversary of Its Invention of the Calculator Texas Instruments press release, 15 August 2002.

- ↑ Electronic Calculator Invented 40 Years Ago All Things Considered, NPR, 30 September 2007. Audio interview with one of the inventors.

- ↑ "Single Chip Calculator Hits the Finish Line", Electronics's', February 1, 1971, p19

- ↑ http://www.spingal.plus.com/micro

- ↑ "The one-chip calculator is here, and it's only the beginning", Electronic Design, February 18, 1971, p34.

- ↑ http://mathcs.albion.edu/~mbollman/CI/loanarranger2.htm

- ↑ http://mathcs.albion.edu/~mbollman/CI/CM.htm

- ↑ http://mathcs.albion.edu/~mbollman/Calculators.html

References

- Hamrick, Kathy B. (1996-10). "The History of the Hand-Held Electronic Calculator". The American Mathematical Monthly (The American Mathematical Monthly, Vol. 103, No. 8) 103 (8): 633–639. doi:10.2307/2974875. http://www.jstor.org/pss/2974875. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- Marguin, Jean (1994) (in fr). Histoire des instruments et machines à calculer, trois siècles de mécanique pensante 1642-1942. Hermann. ISBN 978-2705661663.

- Mourlevat, Guy (1988) (in fr). Les machines arithmétiques de Blaise Pascal. Clermont-Ferrand: La Française d'Edition et d'Imprimerie.

- Taton, René (1969) (in fr). Histoire du calcul. Que sais-je ? n° 198. Presses universitaires de France.

- Turck, J.A.V. (1921). Origin of Modern Calculating Machines. The Western Society of Engineers. Reprinted by Arno Press, 1972 ISBN 0-405-04730-4.

Further reading

- U.S. Patent 2,668,661 – Complex computer – G. R. Stibitz, Bell Laboratories, 1954 (filed 1941, refiled 1944), electromechanical (relay) device that could calculate complex numbers, record, and print results by teletype

- U.S. Patent 3,819,921 – Miniature electronic calculator – J. S. Kilby, Texas Instruments, 1974 (originally filed 1967), handheld (3 lb, 1.4 kg) battery operated electronic device with thermal printer

- The Japanese Patent Office granted a patent in June 1978 to Texas Instruments (TI) based on US patent 3819921, notwithstanding objections from 12 Japanese calculator manufacturers. This gave TI the right to claim royalties retroactively to the original publication of the Japanese patent application in August 1974. A TI spokesman said that it would actively seek what was due, either in cash or technology cross-licensing agreements. Nineteen other countries, including the United Kingdom, had already granted a similar patent to Texas Instruments. – New Scientist, 17 August 1978 p455, and Practical Electronics (British publication), October 1978 p1094.

- U.S. Patent 4,001,566 – Floating Point Calculator With RAM Shift Register - 1977 (originally filed GB March 1971, US July 1971), very early single chip calculator claim.

- U.S. Patent 5,623,433 – Extended Numerical Keyboard with Structured Data-Entry Capability – J. H. Redin, 1997 (originally filed 1996), Usage of Verbal Numerals as a way to enter a number.

- European Patent Office Database - Many patents about mechanical calculators are in classifications G06C15/04, G06C15/06, G06G3/02, G06G3/04

External links

- Programmable calculators Specifications and description of many (programmable) calculators

- On TI's US Patent No. 3819921 – From TI's own website

- 30th Anniversary of the Calculator – From Sharp's web presentation of its history; including a picture of the CS-10A desktop calculator

- Museum of Pocket Calculating Devices - Includes a massive photo gallery of calculators throughout the ages of all different shapes and sizes.

- The Old Calculator Web Museum - Documents the technology of desktop calculators, mainly early electronics

- History of Mechanical Calculators

- Vintage Calculators Web Museum - Shows the development from mechanical calculators to pocket electronic calculators

- The Museum of HP calculators (slide rules/mech. section)

- Soviet Calculators Collection - A big collection of Soviet made calculators

- MyCalcDB - Database for 1970s and 1980s calculators

- Microprocessor and single chip calculator history; foundations in Glenrothes, Scotland

- HP-35 - A thorough analysis of the HP-35 firmware including the Cordic algorithms and the bugs in the early ROM

- Bell Punch Company and the development of the Anita calculator - The story of the first electronic desktop calculator

- Busicom LE-120A "HANDY" electronic calculator

- Photos and descriptions of electronic calculators from the 1970's

- Handheld mechanical calculator photos and manuals

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||